The following paper contains references to trauma, sexual assault, murder sport, and fascism, and spoilers for the Hunger Games series.

As long as you can find yourself, you’ll never starve.

-The Hunger Games

Dystopian fiction is at its highest popularity since the 1960s. The Hunger Games, the first novel in a trilogy by Suzanne Collins that follows the adventures of teenage heroine, Katniss Everdeen, as she fights, first to survive and then to overthrow her corrupt government in a dystopian future America called Panem, is poised to overtake George Orwell’s 1984 as the most popular dystopian novel ever. Dystopian young adult fiction is burning up the bestseller lists and box office rankings — but dystopian fiction has also long been taught to adolescents in schools across the country.

Why?

The Hunger Games series is popular with its teenage audience because they can relate to it as an analogy for adolescence. Teens will relate to any coming-of-age story, but dystopian extremes can counterintuitively feel even more real. Dystopian young adult fiction takes the chaos of adolescent development and transforms it into a narrative which provides both an outlet and a map to the teen audience.

Can neuroscience explain the popularity of The Hunger Games?

Adolescence is a time of dramatic change. From age 10 to 25, approximately, the human brain goes through significant structural transitions as it is both built up through the maturation of the various areas of the cortex and the myelination of neurons, and thinned out through synaptic pruning, a kind of specialization. The teenage brain advances in a back-to-front pattern. The prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for executive functions such as impulse control, emotional response, decision making, planning and judgement, is not considered fully matured until the mid-twenties.

As the brain matures, it undergoes a structural remodeling of gray and white matters. Gray matter, responsible for processing gathered information, thickens throughout childhood and achieves peak thickness in early adolescence or just before. White matter is a kind of service network that connects parts of the brain and carries messages between them. It is made up of axons, nerve fibers that act as information carriers, surrounded by a myelin sheath, white in color, which insulates and protects the axons, allowing faster communication between the different thought processing systems. The better the insulation, the faster the communication. During adolescence the brain loses gray matter and gains white matter as the most frequently used synapses go through myelination and the least frequently used synapses are altered or eliminated.

Teenage brains are developmentally different from adult brains: they are slower to decide because there is too much information to wade through, network connections are still forming, and the prefrontal cortex is still developing.

In the Hunger Games twenty four combatants, one male and one female tribute aged 11 to 17 from each of Panem’s twelve districts, are put into a controlled hostile environment and pitted against each other for however long it takes for all but one to die. Some of the tributes are conditioned for combat to the death since early childhood and have an obvious advantage. Others, like protagonist Katniss, have gained survival skills from their harsh upbringing. Many tributes form early alliances but must ultimately betray them in order to win. Tributes are mentored by previous victors and may also gain sponsors on the outside who can send supplies and cheats to their favorites.

Synaptic pruning works in a similar way. Although there are many thousands more than twenty four synapses in an adolescent’s brain, and the activity is not as contentious, the synapses are chosen to retain space in the adult brain based on what is strong, what is used, and what is learned. Like the tributes, the brain’s prime directive is to survive, and then prosper.

For the most part, fortunately, the teenage readers of the Hunger Games trilogy will never be required to fight their peers or survive an environment created to destroy them. However, they are biologically wired to relate to the struggle of synaptic plasticity or the “use it or lose it” principle. Their brains are making hundreds of thousands of choices based on the same questions of “what do I need to know to survive?” and secondarily “what do I want to know to enjoy?” The older they get, and the more maturely developed their brains are, the quicker the choices are made as the myelination forms over the ‘winning’ synapses and the excess, weaker, unnecessary or redundant gray matter is weeded out.

While the overall volume and thickness of the brain’s gray matter decreases through adolescence the gray matter within the regions that make up the ‘social brain network’ — those associated with the mentalizing process including dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), temporoparietal junction (TPJ), posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), and anterior temporal cortex (ATC) — continues to thicken into the early twenties of late adolescence. This indicates that areas of the brain responsible for deciphering the intentions of other people are still forming throughout adolescence 1. Additional data suggests that adolescents engage their social brain network even when there are no social cues 2 – in other words, teenagers expend energy to consider what others, and especially their peers, may think about everything they are doing or wanting to do. Combined these two ideas explain how teens may get stuck in the decision making process more often than adults or children.

Katniss is quick to make life or death decisions in the arena because her survival skills are well honed. However she has many difficulties deciding what she wants beyond survival. The novels are written in the first person so the reader is privy to all of Katniss’s questions, fears, and self-doubt. She doesn’t trust the society she was born into, the system she must work within, or any of the people she encounters, including her family, her mentors, and her peers. But she also doesn’t entirely trust that distrust or her own point of view.

Katniss begins the series at age sixteen which is the very end of the book’s teen tribute spectrum, but still right in the middle of adolescence in terms of human brain development. Her brain is still maturing, her synaptic social brain network still forming, which leads to her overthinking every decision, every option, and leaves her overwrought. This is frustrating not only for Katniss but for everyone around her and for adult readers who prefer she would decide, and act, rather than ‘whine’ about it internally. But teenage readers in the same developmental stage as Katniss can relate to her indecision and to the pressure she feels from adults, peers, and societal norms. They recognize that the struggle to articulate her desires reflects Katniss is actually moving away from childish egocentrism and toward an adult social engagement and awareness 3.

As Katniss is going through the process of building her own identity, there are many forces around her fighting to do it for her. There are the forces of the Capitol, led by chief antagonist President Snow, who use the spectacle of the Hunger Games to keep the upper class masses entertained and the lower class masses enslaved. There are the forces of the rebellion, led by President Coin, who shape Katniss into the symbol of their revolution. There are the people closest to her, Gale and Peeta, at odds for her affection and representative of different paths of social interaction. And there are many individuals and groups who share traits and outlooks with one or more. And every one of them requests — requires — Katniss to be more than the adolescent girl she is or the adult woman she is becoming.

Adolescents are highly susceptible to external influences, especially peers. They are far more likely to engage in risky behaviors in the company or service of their friends or like minded people 4. The brain learns by taking a concrete sensory experience and moving the data through its cortical network to reflect, observe, consider, and hypothesize, and finally act. Adults make decisions by weighing options, considering various sides, thinking abstractly. Adolescents are not developmentally capable of the same thought processes. They misconstrue external data such as facial expressions and put too much emphasis on peer evaluation 5, worrying ‘what everyone thinks of me’. Katniss’s experience with celebrity in the Hunger Games is a heightened reflection of the teen experience of living in a bubble.

Faction Before Blood: Teenage Self-districting

Adolescence is a period of self-discovery. As teenagers move away from their parents both physically and metaphorically they start to recognize the ways in which their identity is tied to their family, their community, and the beliefs of others. They become more self-aware and start to ask questions about who they are separate from their parents and teachers, who they want to be and what they want to believe in, what type of peer groups and connections they want to foster, and what they want to do with their time, what they want to matter. These are complex questions that require a great deal of both thought and experimentation which results in the adolescents pushing boundaries, questioning values, breaking rules, and taking risks. What adults may consider “acting out” is really an important, healthy, process of exploration and discovery.

During adolescence peer groups start to take precedence over family 6. Young adult fiction often builds this natural tendency into the experience of the characters, and in some cases directly into the structure of the story. In J.K. Rowling’s wildly successful Harry Potter series, the students of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry are sorted into one of four Houses by a magical talking hat. The House system can be found in many real world boarding schools across both England and America, but in Harry Potter the Houses are directly linked to certain attributes the Sorting Hat can sense within the student: Gryffindors are brave and foolhardy, Ravenclaws are intelligent and awkward, Slytherins are ambitious and conniving, Hufflepuffs are loyal and unremarkable.

Readers identify with the various traits, and with the various characters, and choose which House they believe they would be sorted into. In lieu of the magic hat, there are thousands of online surveys which will grant a Hogwarts House based on the participants’ answers, one even designed by the Rowling herself 7. But the author also makes it clear in the text the Hat takes a student’s desires into account and any student may request the House they want 8:

“It only put me in Gryffindor,” said Harry in a defeated voice, “because I asked not to be in Slytherin…”

“Exactly,” said Dumbledore, beaming once more. “Which makes you very different from Tom Riddle. It is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.”

Thus readers may feel secure in their choice.

Veronica Roth’s Divergent series takes it one step further. In the trilogy’s post-apocalyptic Chicago, society is divided into five factions based on their members disposition: Abnegation, for the selfless; Amity, for the peaceful; Candor, for the honest; Dauntless, for the brave; and Erudite, for the intellectual. Factions are chosen at sixteen and while the teens are given a personality test not unlike the online Sorting Hat quizzes to determine their best match, it is entirely up to them which faction they decide to join. Protagonist Tris is coded ‘divergent’ because the results of her aptitude test indicate she has traits from three of the five factions. She chooses Dauntless which separates her from her parents in Abnegation and her brother in Erudite. Tris’s situation fictionalizes many common adolescent anxieties: the desire to fit in and be understood, the need to leave her family which can be both welcome and frightening, the pressure to choose a life path at an increasingly younger age, and the fear that if she is comfortable in more than one area, or doesn’t know which she values most, she is somehow aberrant and lesser 9.

Teens practice self-distracting in many ways outside of fiction — sports, clubs, cliques, tracked classes etc. — but fiction is not as dependent on external influence. Fandom, the peer groups that build up around a certain property, or more simply “people who like the same things I like”, is self-selecting, emphasizes inclusivity, and has no barriers on numbers or geography. The internet allows fandom communities to span the globe and unlike joining a team, there are no tryouts and everyone gets in. While gatekeepers exist, they do not hold any particular power; to be welcome in a given fandom a teen only has to be a fan.

In giant fandoms such as Harry Potter and Divergent subfandoms appear around the Houses and Factions. These divisions represent traits shared by the people within the subfandom — e.g. Gryffindor or Dauntless — and in opposition to the people in other subfandoms — e.g. Slytherin or Erudite. Adolescence is an eternal internal struggle between individuality and conformity. Self-sorting allows teens to choose which of their own individual traits to recognize so they may conform to the group which legitimizes and rewards them.

Self-districting, however, does not do away with external districting. In The Hunger Games, Panem is divided into fourteen areas: the aristocratic Capitol, twelve working class districts, and a wasteland that was once the thirteenth district. Unlike in the other fandoms the characters are born into an area and there is no movement between them. While some characters born in the Capitol choose to join Katniss’s revolution they are committing treason, and no one in the Districts can earn a space in the Capitol, nor choose to leave their District for another no matter how wealthy or successful they become.

Modern America is not as divided as Panem, however, racism and classism are pervasive and color teen choices even as they make efforts to embrace diversity and equality 10. An honors student is likely to value her intelligence, choose to represent herself as a Ravenclaw, and seek out other self-selecting Ravenclaws within her honors classes. Black and Hispanic students are significantly underrepresented in honors classes and often isolated even when present 11. Our Ravenclaw would not consider it racist to befriend only other perceived high achieving students but systematic failures result in her ‘House Pride’ translating to disproportionately white pride. Fandom is an expression of the imaginary but it exists within the real world. As they are navigating it teens are bombarded with societal divisions, ideas, and expectations.

Reflections of Guyland and Girl World in The Hunger Games

When asked, young men and young women alike can present a list of presumed societal guidelines that govern their behavior and attitude. These teens report feeling as if they must follow these “rules” or they will be bullied and ostracized by both their peers and their community of adults. The rules are different for boys and girls, but there are correlations between the two. These rules are passed down by parents, mentors, and the media and they are ever present and seemingly inescapable.

Michael Kimmel’s book Guyland: The Perilous Place Where Boys Become Men lays out a “Real Guy’s Top Ten List” 12 of presumed rules compiled by interviews with 400 ‘guys’ aged 16 to 26, most of them straight, white, and upper middle class, all cis and American.

“Boys Don’t Cry”

“It’s Better to be Mad than Sad”

“Don’t Get Mad — Get Even”

“Take It Like a Man”

“He Who Has the Most Toys When He Dies, Wins”

“Just Do It, or Ride or Die”

“Size Matters”

“I Don’t Stop to Ask for Directions”

“Nice Guys Finish Last”

“It’s All Good”

In the Hunger Games series there are three main men of adolescent age: Gale Hawthorne, Peeta Mellark, and Finnick Odair. All three conform in certain ways to the “Real Guy” vignette as listed above, and all three encourage the audience to examine the “Real Guy” concept. This combination of familiar roles and subversion of same makes the characters particularly relatable to adolescents.

Gale, Katniss’s childhood friend turned freedom fighter, is the clearest example of a “Real Guy” of the three. He explicitly hits nearly every example on the Top Ten list. Gale is introduced as a literal hunter and a provider for his family and community. He is more rebellious and political than Katniss, wanting to take a stand against the Capitol from the beginning and is first to fight back when the rumblings of war begin. Where other characters are driven by despair, fear, hope or love, Gale is consistently driven by anger. In Catching Fire he is caught fighting in a raid of the district’s marketplace and is lashed in the central square as a punishment and warning. Gale ‘takes it like a man’ — “His teeth are gritted and his flesh shines with sweat.” 13 — and it only makes him more committed. Gale maintains his overt masculinity and ‘Action Hero’ persona throughout the series. In the final chapters he is a leader in the war effort and unapologetic about the death of innocents, including children. This end is considered controversial as he is depicted in a morally ambiguous light but he remains a hero to “Real Guys” in the audience.

Gale is one leg of a love triangle between himself, Katinss, and Peeta, her partner in the Games. The three grew up in the same village but while Katniss and Gale spent their days hunting game outside the town barriers, Peeta apprenticed at his family’s bakery. In contrast to Gale’s rage, Peeta is measured and diplomatic. He is not an ‘Action Hero’ and in fact plays the ‘Damsel in Distress’ to Katniss’s ‘White Knight’ on more than one occasion. He is more of a caretaker than a provider and is thus coded feminine rather than masculine. However, Peeta is not without masculine or “Real Guy” traits. His physical strength is stressed, he makes bold moves, and he is willing to do anything to protect Katniss.

In the first Hunger Games he participates in, Peeta allies himself with the ‘career’ tributes who had been trained and groomed to fight in the tournament. With this alliance he is able to keep himself and Katniss alive by sticking close to the biggest threats as they pick off the weaker players. In order to fit in, Peeta must play act a “Real Guy”. In this way Peeta is enacting the process the ‘guys’ reportedly go through in Guyland. Thus Peeta is theoretically, if counterintuitively, positioned to be the most relatable ‘guy’ in the series.

Though not a love interest for Katniss, Finnick Odair is the closest the Hunger Games series has to a romantic lead — the ‘Prince Charming’ type marketed to girls and women. Like Gale he is a warrior and provider, and like Peeta, he is also victimized and allowed to show emotions other than anger. Finnick displays many prescribed behaviors of masculinity: he is fit, brilliant with his chosen weapon, marries and fathers a child, goes down swinging. He is attractive and flirtatious, has charmed the whole country, but his heart belongs to one delicate woman. He’s not as rugged as Gale but ‘guys’ can relate to him, and he makes young women swoon within the story and the audience.

But Finnick’s story also subverts the “Real Guy” stereotype. He is a kind of spy, dealing in secrets and playing both sides. He is also a victim of sexual assault. Since winning his Hunger Games, Finnick was sold as an ‘escort’ to rich donors by President Snow. Finnick uses the opportunity to gather intel for the resistance which is a move far more Black Widow than James Bond. Finnick uses his charm and his body to collect gossip, taking it not like a man, but like a woman. Finnick also shows ‘weakness’ in his emotions, openly crying and showing both fear and love.

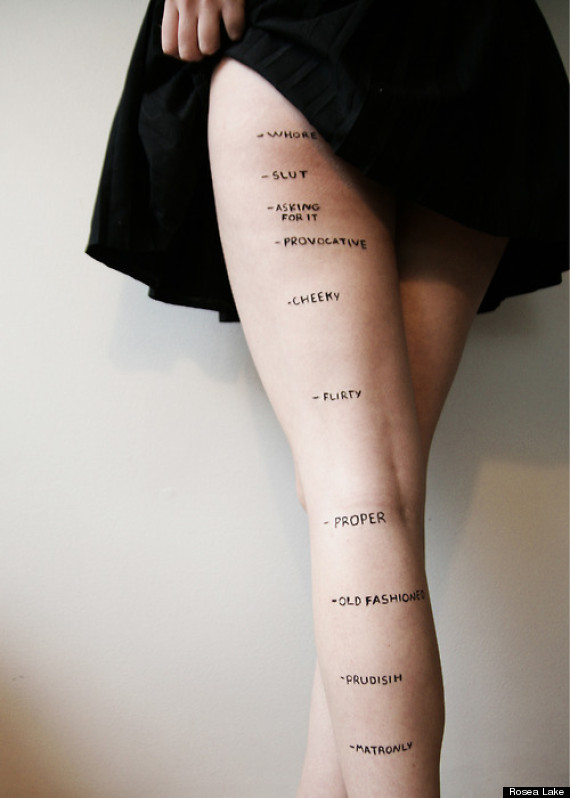

Rosalind Wiseman’s Queen Bees & Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and the New Realities of Girl World does not provide a Top Ten List of “Real Girls” guidelines and has stated that not only do girls most often encounter rules by breaking one, the rules are different for different girls 14. Moreover many of the ‘rules’ of “Girl World” can be described as contradictory. In the image below artist Rosea Lake 15 makes the point that there is no length of skirt a young woman may wear without judgement:

The Hunger Games series certainly addresses the regulation of appearance as each tribute is assigned a stylist and team of people tasked with making them as attractive to the Capitol’s elite as possible in order to obtain sponsorship which translates to help in the form of tools, medicine, or food while the Games go on. The social game does not come easily to Katniss who is described as “sullen and hostile” by her mentor. She later watches one of the other tributes, “one of the giants, probably six and a half feet tall and built like an ox” 17, perform and reflects “If only I was his size, I could get away with sullen and hostile and it would be just fine!” 18. Katniss is aware of the rules and vacillates between attempting to follow them and defiantly rejecting them to varied results. Her instincts, more often than not, guide her to follow the rules of “Guyland” rather than “Girl World”. But this is less subversive than Peeta or Finnick being coded feminine in some areas. “Girls can wear jeans/And cut their hair short/Wear shirts and boots/’Cause it’s OK to be a boy/But for a boy to look like a girl is degrading/’Cause you think that being a girl is degrading” 19. Many girls in “Girl World” and “Guyland” set themselves apart as ‘not like other girls’ which translates to ‘better’ because they also think that being a girl is degrading.

Johanna Mason explicitly states that she is “not like the rest of you” 20 in response to Katniss and Finnick’s emotional reaction to recordings of their loved ones being tortured, and she spends the series proving it. In fact, Johanna shares the most in common with Gale and his “Real Guy” credos – but as a woman she cannot actually be a “Real Guy”. Johanna is a reflection of the anger young women feel to conform to rules that are not even laid out clearly, and the anger they are taught not to admit to, or preferably, not to feel at all.

The Hunger Games series provides its teen audience with many examples of reactions to the uncontrollable emotions of adolescence coupled with the societal expectations that police those reactions and emotions. Johanna is one extreme and Annie Cresta is another. Annie is introduced as driven mad by her experience in the Hunger Games. She is presented as requiring rescue in her first appearance — her one time mentor, Mags, chooses to take her spot in the special Hunger Games made up of former winners. Annie is held hostage through most of the action, both physically and mentally. She is used as bait and tortured to attack and control her lover Finnick. When finally reunited they immediately marry and conceive a child and it is suggested love and family ground her so she does not retreat into madness again at his death. Annie is described as Finnick’s “poor, mad girl back home” 21 and clearly suffers from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. She is a warning but also, in her quiet way, she allows girls who prefer to curl into their emotions and avoid the traumas and tragedies of “Girl World”, real or imagined, the hope they can and will survive it.

Primrose Everdeen, Katniss’s younger sister, is the most recognizably feminine of the adolescent characters in the series. As one of the youngest characters she is innocent, a Spring maiden. Like Annie, the first action surrounding Prim is someone — Katniss — volunteering to take her place in the Games, indicating she is in need of protection. She is described as fair and pretty with gentle features, unlike her sister who more resembles their father and the masculine Gale. They are also dissimilar in personality: Prim is kind, compassionate, empathetic, friendly, warm, eager. Where Katniss can struggle to make friends, everyone loves Prim. Katniss is a hunter and Prim is a caretaker. In the terms of Wiseman’s book, Prim is presented as a “Floater”, what the author considers the best option with the most optimal outcome in “Girl World” 22. But in the dystopian world of The Hunger Games, Prim is selected to fight to the death, bombed into near oblivion, and finally killed by friendly fire. “I don’t think there are real Floaters,” says Liza, reported by Wiseman, “Maybe I’m just bitter, but most of the time they are too good to be true.” 23 In Prim’s case she is too good to survive.

None of the adolescent characters presented in the Hunger Games series follows all the rules of “Guyland” or “Girl World” and many of them push the boundaries in ways that bring up interesting questions and encourage thoughtful discussion. The adolescent audience responds to both the questions and the exaggerated but recognizable reflection of their own realities.

Empathy and Activism Through Fandom

Adolescents don’t have the vocabulary or life experience to express themselves with depth so their fandoms become a kind of shorthand. This can be a powerful tool, though it may also obscure the message.

The Hunger Games series is about children aged 11-17 forced to fight to the death for the entertainment of the aristocracy and the subjugation of the poor. The books topped the best seller lists for years and the films place in the top 35 of all time domestic box office gross — the first two films are ranked 17th (The Hunger Games) and 12th (Catching Fire) 24. The final book and the last two films relate the revolution and its consequences rather than the Games, they ask the audience to think about violence and do not include arena fights to the death, and they are the least popular. With the last adaptation now in theaters, the studio is considering prequels that will take the story back to the Games 25. The audience of The Hunger Games, like the Capitol audience of the Hunger Games, finds gladiator duels to the death more entertaining and less upsetting than visions of poverty, injustice, and war, and the studio is excited to monetize that desire.

The Hunger Games brand encourages the audience to relate to the Capitol in more explicit ways as well. Cover Girl marketed a line of cosmetics based on the Districts, however in the story canon it is the citizens of the Capitol who wear outlandish make-up. The people of the Districts do so only when they are tributes in the Games. Many found the ads disturbing, but they did not dig too deeply into why their suggestion is uncomfortable.

One billion children worldwide are living in poverty 26. In the United States 21.1% of children under the age of 18 are living in poverty 27. Hunger is the number one cause of death in the world 28. There are an estimated 250,000 child soldiers in the world, 80% of them under the age of 15. The youngest reported child soldier was 5 years old 29. Many child soldiers volunteer, or are volunteered by their family 30. The dystopia of the Hunger Games series already exists in these forms but like the Capitol, the audience would prefer not to think about it.

However, teen fans of these series are also inspired to action. A group of young fans who grew up with Harry Potter formed a non profit organization in his name 31. Since 2005 The Harry Potter Alliance (HPA) has used both the Harry Potter series and the Hunger Games series to engage fans in organized campaigns to combat inequality, poverty, and illiteracy. The HPA is a small organization with modest achievements but it was founded by adolescents who believed they could use the values they found in books to change their world for the better and over the past ten years they have proven it to be true. Adolescent “coming of age” translates to realizing how unfair the world is. It’s scary and infuriating, and it spurs many teens to action even if it is just arguing with authority or taking a selfie as part of a campaign against photoshopping celebrities.

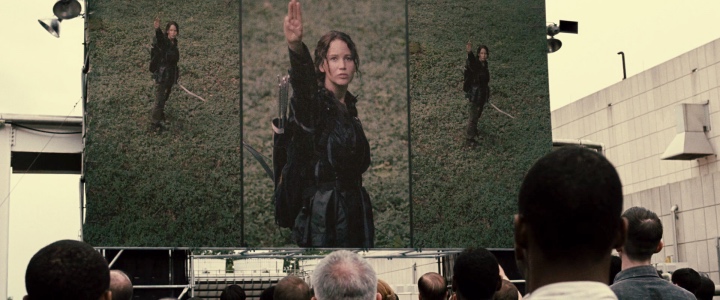

In 2014 Thailand’s military took over the government and imposed martial law. Political meetings of more than five people were banned by the new regime but university students gathered to protest, using the Hunger Games three fingered salute to rally. The film and the salute was subsequently banned in Thailand but the images of Thai protesters reenacting Katniss and Panem’s defiance became international news 32. American teens cannot easily relate to the military takeover of the government of Thailand, but they can relate to The Hunger Games and recognize that the Thai students use of District Twelve’s salute indicates a real world injustice.

These stories connect teenagers to each other and the world around them, they provide analogies and vocabulary for teenage expression, and they encourage teen readers to define their own passions and struggles. Dystopian young adult fiction gives adolescence and adolescents a voice.

Notes

- Blakemore and Mills, 2014

- Dumontheil et al., 2012

- Van der Bos et. al, 2011

- Blakemore, 2014

- Blakemore, 2014

- Blakemore, 2014

- Pottermore

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, p. 333

- Scholes and Ostenson, 2014

- It’s Complicated, Chapter 6

- National Center for Education Statistics

- Guyland, p. 45

- Catching Fire, p. 115

- “Defining Girl World and the Rules Therein” kidsinthehouse.com

- photograph copyright Rosea Lake, http://roseaposey.tumblr.com

- The Hunger Games, p. 116

- The Hunger Games, p. 126

- The Hunger Games, p. 126

- “What It Feels Like for a Girl”, Madonna

- Catching Fire, p. 347

- Catching Fire, p. 348

- Queen Bees & Wannabes, p. 30-31

- Queen Bees & Wannabes, p. 30

- BoxOfficeMojo.com

- VanityFair.com

- DoSomething.org

- census.gov

- DoSomething.org

- JusticeSociety.org

- WarChild.org.uk

- TheHPAAlliance.org

- NYTimes.com

References

Collins, Suzanne, The Hunger Games (2008)

Collins, Suzanne, Catching Fire (2009)

Collins, Suzanne, Mockingjay (2011)

Rowling, J.K., Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1999)

boyd, danah, It’s Complicated: the social lives of networked teens (2014)

Jetha, Michelle and Segalowitz, Sidney; Adolescent Brain Development (2012)

Kimmel, Michael S., Guyland: The Perilous Place Where Boys Become Men (2008)

Wiseman, Rosalind, Queen Bees & Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and the New Realities of Girl World (2002)

Blakemore, S-J, Mills, KL. “Is Adolescence a Sensitive Period for Sociocultural Processing?” 2014. Annu. Rev. Psycho. 65:187–207

Dumontheil I, Hillebrandt H, Apperly IA, Blakemore S-J. 2012. “Developmental

differences in the control of action selection by social information.” J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24:2080–95

Scholes, Justin and Ostenson, Jon; “Understanding the Appeal of Dystopian Young Adult Fiction” 2013. The Alan Review. Vol. 40 No. 2

https://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/ALAN/v40n2/scholes.html

van den Bos W, Van Dijk E, Westenberg M, Rombouts SA, Crone EA. 2011. “Changing brains, changing perspectives: the neurocognitive development of reciprocity.” Psychol. Sci. 22:60–70

“All Time Box Office Domestic Gross”, Box Office Mojo

http://www.boxofficemojo.com/alltime/domestic.htm

(visited December, 2015)

“11 Facts About Global Poverty”, Do Something.org

https://www.dosomething.org/facts/11-facts-about-global-poverty

(visited December, 2015)

“What We Do”, Harry Potter Alliance

http://www.thehpalliance.org/what_we_do

(visited December, 2015)

“Child Soldiers”, Justice Society

http://justicesociety.org/ishmael/

(visited December, 2015)

“Defining Girl World and the Rules Therein”, kidsinthehouse,

http://www.kidsinthehouse.com/teenager/social-life/friends/defining-girl-world-and-rules-therein, (visited October, 2015)

“Achievement Gaps”, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/studies/gaps/

(visited December, 2015)

“Thai Protesters Are Detained After Using Hunger Games Salute”, New York Times,

(visited December, 2015)

“Child Soldier”, WarChild.org

https://www.warchild.org.uk/issues/child-soldiers

(visited December, 2015)

Anika Dane

SOCS 686 Adolescent Brain Development

Fall 2015